On Sunday, I spent several hours at Yad Vashem - Israel's official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust. I had brought my students there as part of a multi-day visit that included guided tours, workshops, and conversations with the institute’s researchers on the role of Catholic clergy in saving Jews during World War II. I’ve visited Yad Vashem countless times, yet I always find something new to learn, and I always leave with more questions about one of the 20th century’s most horrific atrocities.

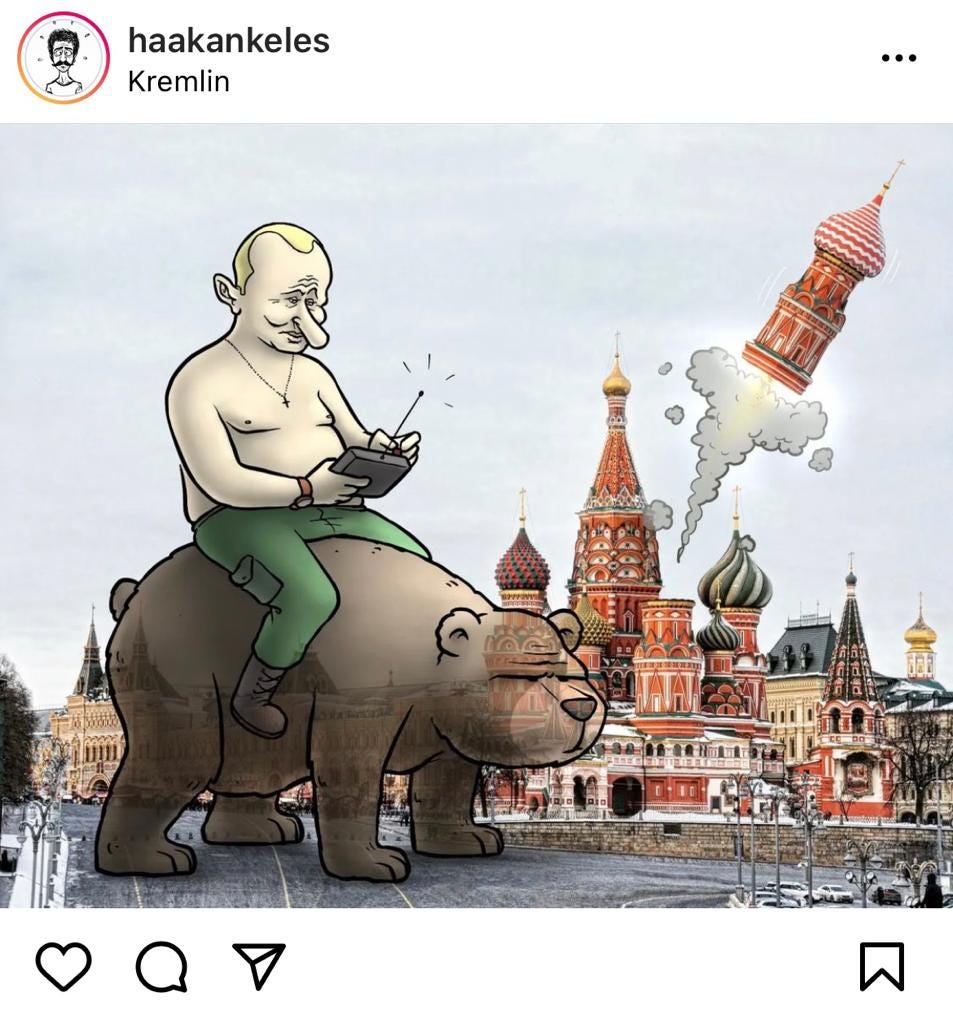

In this space intentionally designed to raise questions about human nature and the arc of history, it was difficult not to connect the events of the past with contemporary headlines. On Sunday, the dark clouds of war hung heavy over the border between Ukraine and Russia. World leaders scrambled to conjure last minute diplomatic proposals that could potentially stave off what to me felt like an inevitability: a Russian invasion.

Now, in recent years there has been much debate about whether it is appropriate to make comparisons between our times and the era of leading up to World War II. I believe that is is sometimes easier - and even lazy - to label things in such extreme terms because from the Western (and perhaps global) perspective, the Nazis serve as a historical example where the difference between right and wrong is plainly obvious. Therefore, utilizing such terminology establishes a discursive binary between good and evil that can potentially delegitimize and disarm the position of your political opponent. This can be a slippery slope. As Anti-Defamation League director Jonathan Greenblatt remarked in 2017, “misplaced comparisons trivialise this unique tragedy in human history.” Worse, if you call everything the second coming of Hitler you may find yourself in a similar position as Chicken Little, whose cries fell on deaf ears when the sky really, truly was falling.

Let there be no doubt. The sky is falling. Just ask the residents of Kyiv, Kharkiv, and countless other cities across Ukraine, who spent the last few days making hurried arrangements to flee their homes or were huddled together in the metro stations as Russian missiles hit the earth above them. Just ask the neighboring countries of Moldova, Romania, and Poland that are setting up camps to intake refugees from the battlefield.

Russian president Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine is an effort to reassert Russian geopolitical power after the collapse of the Soviet Union. When the Soviet Union collapsed, and Ukraine (along with other republics) declared its independence, some scholars - like Francis Fukuyama - believed that humankind had arrived at the end of history. Progress had paved the way for a liberal democratic future. It was the end of communism, the end of apartheid, perhaps the end of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Three decades later it is clear that we have neither reached history’s end nor guaranteed a brighter, more democratic future. Following a decade-long swoon, Putin has slowly but surely brought Russia back to the world stage, repeatedly challenging the independence of former Soviet republics and the legitimacy of their governments. This isn’t the end of history. As Winston Churchill put it, “It is not even the beginning of the end.” [Insert cliché here,] We are living history.

What does Putin want? Will he be satisfied with only the capture of Ukraine and the establishment of a puppet regime in Kyiv? How will the US and her allies respond? Are sanctions enough to stop Putin, and how long will it take to see meaningful results? Will this empower authoritarian regimes elsewhere in the world? Is there an “off-ramp” that can prevent further carnage? How will this impact the global economy? The price of gasoline? Supply chains? Commercial air travel? While I study geopolitics, and track these events with great interest and detail, I don’t know the answer to these questions.

These questions are important, but what matters most to me today is the fate of ordinary Ukrainians.

Today I wonder: what can be done to help them, provide them aid, safe passage from the battlefield, support and hope as their world collapses, and - in the event that this dark chapter continues in the months and years to come - enable them to once again have an independent state?

Of the many topics that one wrestles with at Yad Vashem, one that challenges me the most is the stories of the Righteous Among the Nations, those individuals who “protected their Jewish neighbors at a time when hostility and indifference prevailed.” I’m challenged by their stories because although I believe that I am a good person, the scarcity of Righteous Among the Nations during WWII underlines that being a good person doesn’t necessarily mean that you’ll take action when the time comes, that you’ll put your own life at risk for the sake of a stranger.

It is therefore inspiring and encouraging to see that - unlike in WWII, where the Nazis had successfully silenced and diminished all of their domestic opponents prior to assaulting the sovereignty of their neighbors - Russian citizens took to the streets of Moscow and Saint Petersburg last night in protest their government’s decision to invade Ukraine. In fact, there were protests all over the world in front of Russian embassies. These voices matter, and could potentially grow.

As I write this newsletter, Kyiv has already been infiltrated by Russian troops. By the time you read this sentence, the government may have already been overtaken by force of arms. But as of today neither you nor I are at risk. So how can we make a difference? How can we be inspired by those who are making their voices heard, and help bring light to others in times of darkness, especially when we don’t know how long this night will last?

This is not an exhaustive list, but here are some ideas. If you have sources, names of organizations, suggestions - please send them my way and I’ll be happy to distribute them in my next newsletter:

Timothy Snyder is a professor of history at Yale University and an expert on the history of WWII in Eastern Europe. Read his recent substack newsletter on ways to help Ukrainians. “Ukraine is not a rich country,” he writes. “The average household makes less than $7000 a year. A little money, sent in the right direction, can make a meaningful difference.”

HIAS works alongside Right to Protection (R2P) in Ukraine and has a long, proud history of providing humanitarian aid and assistance to refugees. There are at least 1.5-2 million internally displaced people in Ukraine at present. That number will undoubtably rise as the conflict continues.

Consider supporting the Ukrainian free press, and in particular following the Kyiv Independent which is providing English-language news on a minute-to-minute basis. Disinformation is one of the central tactics to undermining government legitimacy and public morale, so the work that journalists are doing in Ukraine - and elsewhere around the world - is essential to keeping authoritarianism at bay.

READ AND SPEAK UP. Don’t let the J.D. Vances of the world get the last word. The more informed and vocal you are the more your local and national representatives will consider your positions. That’s how democracy works.

And with that, some content to read:

Joshua Yaffa’s February 24 dispatch for the New Yorker.

“A Bad Day in Kyiv,” by John Sweeney in Newlines Magazine.

“I’m in Kyiv and awake at the darkest hour” by Nataliya Gumenyuk in The Guardian.

“Calamity Again,” by Anne Applebaum in The Atlantic.

“Vlad the Invader,” by Niall Ferguson in The Spectator.

“Putin’s New Iron Curtain,” by Julia Ioffe in Puck.

Serhii Plokhy’s January 2022 exposé on Russia-Ukraine relations in the Financial Times.

Stephen Kotkin’s 2016 piece in Foreign Affairs, where he wrote, “Unlike Stalin, Putin does not recognize the existence of a Ukrainian nation separate from a Russian one. But like Stalin, he views all nominally independent borderland states, now including Ukraine, as weapons in the hands of Western powers intent on wielding them against Russia.”

and this Twitter thread:

I hope you find this week’s content engaging. Take the time to read through the various pieces I’ve chosen to share, and feel free to share this newsletter with others.

Gabi