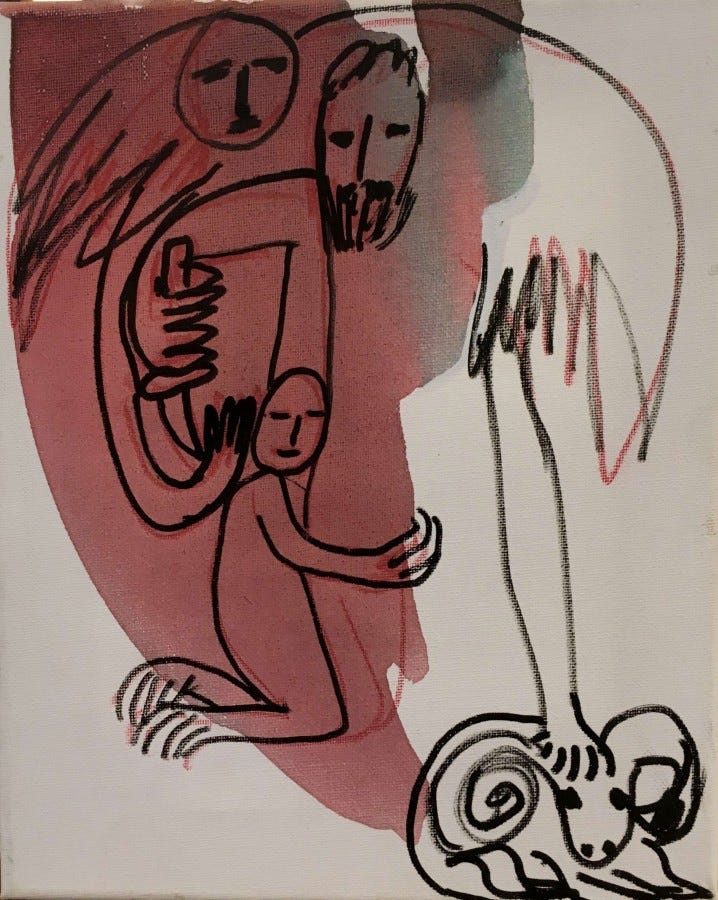

As is typical of Jewish holidays, the Jewish New Year or Rosh Hashanah, serves multiple purposes. It is Yom Harat Olam - the Day the World Was Born - the anniversary and celebration of creation. It is Yom HaDin - the Day of Judgment - when our actions are weighed by God, and, depending on our merits, we are inscribed either in the Book of Life or the Book of Death. It is Yom HaZikaron - the Day of Remembrance - when God reviews our past deeds and we engage in introspection and repentance. In this process, we also recall God’s covenant, both through the retelling of the Binding of Isaac or Akedah and through the blowing of the ram’s horn, the shofar. The shofar’s piercing call serves as a thread connecting all past human experience to the present moment and to the approaching Day of Atonement, Yom Kippur, when God’s judgment is sealed.

The Akedah is arguably one of the most important - if not the most important - texts in the Bible. In Second Slayings (2019), David N. Gottleib argues that Akedah was “the defining moment, the ‘chosen trauma’ of Jewish identity” through which Judaism learns to cope with and overcome moments of crisis. In Anthony Julius’ Abraham: The First Jew, he describes the Akedah as, “a narrative reductio ad absurdum” (a story in which a proposition is disproven by logically extending its implications to an absurd conclusion), that creates space for dialogue and even coexistence between competing Jewish values. Over the centuries, nearly every major and minor Jewish thinker and communal leader has offered commentary and interpretation of the Akedah’s meaning, producing a virtually limitless library from which one can draw knowledge and wisdom.

In that spirit, I would like to share some thoughts on the Akedah that my father-in-law and teacher, Rabbi Eric Cytryn, presented at our synagogue in Jerusalem just a few days ago; reflections that touch on the timelessness of the Binding of Isaac and its contemporary value during a period of crisis that requires sacrifice. I always enjoy learning from Eric, because he finds ways of infusing poetry and music into his understanding of Jewish text and tradition, and this occasion was no different. I hope you finds his insights as compelling as I did.

Shannah Tova.

The Akedah, the Binding of Isaac, means different things to different people at different stages of our lives.

Our lives as individuals, as members of a community, as members of a people, and citizens of a nation, all play into our interpretation and internalization of the Akeda.

In studying the Akedah over the years, I appreciate the need of every generation of our people to interpret the actions of Abraham, Isaac and Sarah based on their own historical predicament, their historical reality.

Perhaps the authors of the Akedah, and the editor who placed it immediately following the expulsion of Ishmael, meant for the Akedah to stand as a subversive sequel to the story of Yiftach, who in the Book of Judges pledged his daughter as a sacrifice to God for a military victory. Yiftach allows the sacrifice to proceed, which was the acceptable practice during at least part of the Biblical Period.

In the Akedah we can see, perhaps, a precursor to the prohibition against human sacrifice on the official Israelite cultic altar later to be established on the same Har HaMoriyah where Jerusalem’s temples stood.

Perhaps, the Jews, primarily during and since the Middle Ages, had it right in interpreting the Akedah as a story meant to console us. Taking note that Isaac is strangely absent from Abraham’s descent from Moriah, authors whose own children had perished at their own hand and the hands of their enemies, during the rampage of Crusader armies through Ashkenaz, suggested that perhaps the Angel came too late, or Abraham didn’t hear him clearly - and Isaac was sacrificed on Moriah’s Altar and soon after brought back to life. They suggest that Isaac was killed, as were many Jewish children during the Crusades, and the Inquistion, and the Shoah, and today. In this reading of the Akedah, Isaac was resurrected after a few days. Perhaps today we also need the comfort these Midrashim (interpretations) gave our ancestors.

Speaking of “we.” In the State of Israel, for us living here and now, the Akedah is the most influential Biblical passage quoted and alluded to in Modern Israeli poetry. For us, it is not an old story, not one consigned to antiquity, the ancient past. Because we are surrounded by enemies who do want to destroy us, our children, and grandchildren, we send them off to the Army, to defend us.

Just a few examples:

The great Israeli poet Haim Gouri, concludes his poem “Yerusha - Heritage”

With the lines:

“Yitzhak, it is said, was not offered as a sacrifice.

He lived a very long time,

Seeing the good, until the light of his eyes dimmed.

But he bequeathed that hour to his descendants.

They were born

With a knife in their heart.”

Could the inevitability of war and sacrifice we experience here be genetically transmitted, generation to generation?

Yehudit Kafri is another of Israel’s great poets. In her poem, “In the Beginning,” Sarai’s (Sarah) dissenting maternal voice is raised, questioning this tyrannical God who only at the last moment defended her son’s life. I think this poem is asking today’s mothers, “Why don’t we demand the life of every child be saved? Send rams into battle, not children!!!”

And from our post October 7 reality, a poem by a young poet, Shachar Ballut, titled “Akedah”:

Like his father, Ishmael is holding the fire and the knife

And there is no one to say:

“Do not raise your hand against the boy”

And there is no angel to cry from heaven:

“Now I know you do not fear God”

There is no one:

Not an angel

Nor a seraph

Only a strong hand raised

Just a mother begging:

“Do not do anything to him”

And You did not withhold

I am the ram in the thicket caught in a bitter land flowing with milk and honey

I am the woman wishing for a sacrifice in place of her sons I am a strong arm

I am Sarah who arose in the morning and Isaac was gone.

Abraham Joshua Heschel a philosopher, a poet, a scholar of Biblical, Rabbinic and Hasidic Literature and, to many, the model for the Rabbinic Social Activist in the 1960’s, was also an anti-Vietnam War activist. At an anti-war rally he told the following story from his youth. When he was 7 years old, he first studied the Akedah. He remembered that as his teacher shared the troubling story with the class, Heschel sat on the edge of his seat, anxiously waiting to hear the conclusion. “At the last possible instant,” the teacher taught, “a heavenly voice called out and saved Isaac and his father from tragedy.”

Suddenly, he, Abraham the child, began to cry uncontrollably. The teacher was confused by his student, closed his book and came over to console young Abraham.

“Why are you weeping, child? Don’t you realize Isaac was rescued?”

Tears streaming down his face, Heschel asked, “But suppose the angel had come a second too late?”

The teacher put his arms around Abraham Joshua Heschel and assured him, “Abraham, Angels are never late.”

At this anti-war rally, some 60 years later, Heschel told this story, but ended it with the insight that while angels are too never late to intervene to save lives...humans are often too late - especially when it comes to preventing violence, bloodshed and warfare.

Shannah Yoter Tova, May this Year be better than last.

Thanks for taking the time to read. As always, I welcome your comments and questions.

Best,

Gabi

Thank you Gabi for sharing Eric’s words. It is always inspiring to learn from him.

Happy New Year.